Food in Fiction

28 February 2024

When I was invited by Granite Noir, Aberdeen’s Crime-writing Festival, to lead a workshop, I was dubious. I’ve taught many things over the years (cookery/French/piano), but I’d never taught creative writing. And though I’ve written 6 novels, I still feel food is what I know best. So I came up with a title for the workshop - ‘Food and its place in Fiction’. They liked it, so I’d no choice but to accept.

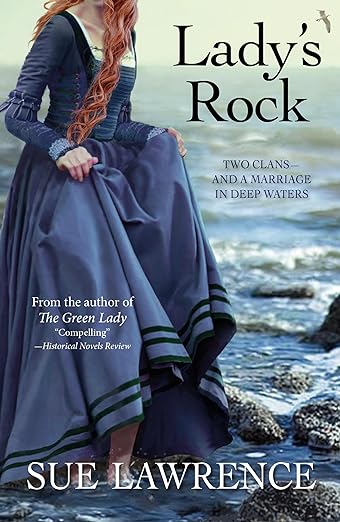

In my previous novels, I’ve used food sometimes to comfort, sometimes to control, sometimes to taunt; and also, sometimes to kill. In my latest book ‘Lady’s Rock’, set in the Scottish islands in the early 16th century, when my main character discovers the plans her husband has for their child, she decides drastic measures are required. And if this entails accumulating local knowledge of potentially poisonous plants, then so be it.

Food in fiction has been used for many reasons. It’s been used to celebrate: think of the cloutie dumpling ‘sugared and fine’, in Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s ‘Sunset Song’ or the magnificent roast goose in Emile Zola’s ‘L’Assommoir’. It has been used as a means of heightening emotions and passions hitherto unknown: think of the fabulous scene withe the quails in rose petal sauce in Laura Esquivel’s ‘Like Water For Hot Chocolate’ - or the elaborate dinner in ‘Babette’s Feast’ by Isak Dinesen. Both are transformative and life-changing.

Food can also be used to give the reader a sense of place. Iain Banks describing the simple breakfast rowie (also known as butterie) places his novel ‘Stonemouth’ very firmly in Aberdeenshire. The fish in Ingrid Persaud’s ‘Love After Love’ – cascadoux - is popular in Trinidad, and the evocative description of the dish transports the reader to the heat of the Caribbean.

Used wisely, food in fiction can build emotions to add colour to a character or to enhance the tension and the passions in a scene. Used as a welcome comfort and as nourishment, it can serve to keep a narrative grounded. It can also help the plot develop: when used as a poison, it can result in an entire family overwhelmed in grief, causing such pain, there seems no way out.

And that’s when the reader must trust in the author to navigate through the hardships or torments that might follow. Whether food is used as benign or malignant in a novel, it is in the author’s hands as they create something – hopefully delicious – for the reader’s delectation.

There was an excellent article published in 2007 in The New Yorker by Adam Gopnik who reminded us about the recipe books meant to be read as novels. He cites Alain Ducasse’s recipe for thrush breasts with giblet canapés on a porcini marmalade. He insists we’re not expected to cook this; rather, to admire the literary skill required to bring it all together. We’re not about to cook this, he writes, ‘any more than we are about to throw ourselves under the train with Anna Karenina or sleep with Madame Bovary.’

I divided the 20 workshop participants into groups of 5, so they could ‘feed’ back to each other; only one was brave enough to read aloud to everyone. Exercises included writing a restaurant scene in first person, then third person to see which of the five senses shone more. I had extracts from Grassic Gibbon, Zola, Esquivel, Dineson and of course the fabulous macaroni pie scene from Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa’s The Leopard. They had pictures from cookery books of diners together, as prompts to write.

Finally, they wrote about transformation of character(s) through food, in first or third person. One man’s poignant piece was about liver: as one of five children, he had to plough through dry, tough liver weekly. Apart from the parents, they all loathed it. So his decision, decades later, to try a dish of liver in a pub, was brave. He was blown away, his aversion transformed into delight when, for the first time, he tasted liver as it should be: moist, tender and delicious.